The White Terror

When we were in Taiwan in July, a family friend took us to a site that may not be in all the guidebooks yet. It was a new Human Rights Museum that has been created from an old detention center for political prisoners in Taipei. Our friend had arranged for an English-speaking tour guide named Stephen to meet us and give my husband and me a personal tour of the facility.

The museum tells the story of the White Terror in Taiwan. Many people don’t realize that, while the communists were establishing their revolutions and political suppressions in mainland China, the Nationalist Chinese government that the communists had defeated (and that was supported by the U.S.) moved to Taiwan and established 38 years of martial law there. Paranoid that communists and other opponents would infiltrate Taiwan, the Nationalist Party government created a system of political and cultural suppression that is now known as the White Terror.

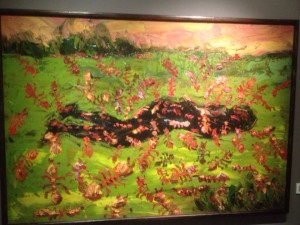

We were taken through the museum to see courtrooms that sent men and women to execution without a fair trial, cells that housed too many inmates in inhumane conditions, visitation rooms where prisoners often saw their family members for the last time, and an exhibition of paintings depicting various graphic moments of torture experienced by prisoners.

At one point, Stephen told us about how political prisoners were treated after they left the detention center. For the rest of their lives, they had trouble finding housing and jobs because of the permanent political prisoner label on their record. As soon as Stephen told us this, I replied that it is not unlike how felons are treated in the United States today. We discussed this for a moment, and I gave him the name of Michelle Alexander’s book, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Stephen said he was eager to read this book about the human rights problems in the United States.

At the end of our tour, Stephen asked if we had any questions. I couldn’t help myself. I know that the way Taiwanese history is told in Taiwan is extremely controversial and political. The Nationalist Party is not some old, defeated regime. It is still one of the most influential political forces in Taiwan, and its Party loyalists do not like discussing the White Terror.

In fact, the reason I was in Taiwan was to attend to the funeral rites of my own father, who was himself a member of the Nationalist Party. My dad was a veteran of the Nationalist military and owed his own escape from China to the Nationalist government. He was loyal to the Party until the day he died and would have been livid to know that I was consorting with people telling stories of the White Terror.

So I couldn’t help but ask: What about the Nationalist side of the story? Were all Nationalists oppressors? Was my dad an oppressor for being loyal to this government? Having known my father, I can understand how the traumatic experiences of exile, the paranoia of war and survival, and the gratitude to a government that literally gave you salvation could lead to the kind of blind loyalty my father and many others like him have for this party. I worried that this museum could be very divisive and one-sided. How am I, the daughter of a man who owes everything to this party, to feel about this place?

And, as a Christian, I am called to promote reconciliation and peace. As Paul writes in Ephesians, “[Christ] is our peace; in his flesh he has made both groups into one and has broken down the dividing wall, that is, the hostility between us.” (Ephesians 2:14) So, given the divisive politics of modern Taiwan around its own history-telling, I wondered: How was this museum breaking down hostilities and promoting peace?

I was grateful that Stephen heard my questions with compassion. One answer he gave was that soldiers like my father were some of most common victims of the White Terror. Because they had the closest ties to mainland China, they were often the first to be suspected of communism. And because they had no family in Taiwan, they were the easiest to dispose of. I remembered then how the government paranoia had affected my own family. My family left my father’s beloved Taiwan partly because the Nationalist government had started getting wary of church missionaries, and my mother–a Methodist missionary–began to fear deportation, which would separate our family.

This reminded me that there are no winners and losers when it comes to injustice and conflict. We are all losers as long as there is hurt and violation and killing.

50 years ago at the March on Washington, which many of our church members are about to commemorate in D.C., Dr. King looked out on the crowd and saw the so-called “oppressor”. And he said, “Many of our white brothers [and sisters], as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny and they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.”

As you look at the conflicts in your own personal life and in our world today, how can you move past winners and losers? How might your actions change if you think about conflicts in terms of a common destiny, peace, and reconciliation?

Asia is full of terror that most people are completely unaware. I did an advanced, primary study of the Cambodian genocide, which has changed my life completely. If you are interested see my website. http://www.yearzeroscreeenplay.com/