Strange Customs

I preached the following sermon at Yale Divinity School’s Lunar New Year worship service at Marquand Chapel on January 31, 2014.

“Gōngxǐ Fācái!” A Mandarin blessing my family used to say at Lunar New Year….And that about concludes my knowledge of Lunar New Year!

“Gōngxǐ Fācái!” A Mandarin blessing my family used to say at Lunar New Year….And that about concludes my knowledge of Lunar New Year!

I was super excited and honored to be asked here for this occasion, and I wrote an email back to Christa to say how much I would love to come and preach at Marquand for Lunar New Year, and I hit send, and then I started dreaming up all the things I could talk to you all about…and then I realized I know basically nothing about this holiday!

But I thought, You know what? Since I was a student, I’ve always thought that being asked to preach in Marquand is like becoming best friends with a magical talking unicorn who just says nice things about you all day to important people. By which I mean it’s a pretty cool and rare thing, and you should probably always take advantage of it! So I thank Christa and Katie and ASA for inviting me to preach today while also acknowledging that I completely tricked you into thinking I would have a lot of wisdom to share about Lunar New Year when I really know nothing!

Mostly because, though my dad is Chinese, I grew up in the middle of Missouri surrounded by white people. So I learned about Lunar New Year the way most kids do in the American midwest–from paper zodiac placemats at the kinds of Chinese restaurants that basically only serve fried chicken doused in “Asian-like” sauces.

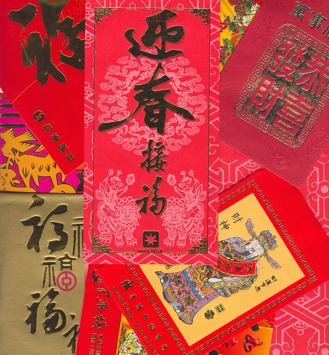

I do have a few other vague memories of Lunar New Year-y things. My parents did give me those red envelopes every year with money in them–and that was pretty cool. And I remember my dad used to have these giant red and black posters with raised velvety Chinese characters on them. And he would put them up all over our basement without any explanation. And I never knew what they said or meant, but I think they were related to the New Year somehow…

So, for me, Lunar New Year was always this vague, strange ritual from another world that didn’t relate to me or my life–some remnant of a past that belonged to my dad but not to me.

And a lot of my experiences with Chinese culture–and a lot of my experiences with my dad–generally felt like that when I was growing up. Dad and his weird Chinese customs were something strange that I tolerated but tried not to talk to my friends about. While other dads grilled out and watched football, my dad cooked tofu and meditated for hours in the living room. While other dads teased their kids’ friends, my dad cornered my friends and gave them a lecture about how Vicki is supposed to be focused on school and not boys. My dad was so embarrassing! He slurped and burped at restaurants. He chased me around the house trying to put Tiger Balm on every ailment. And every few weeks, he would sit me down and lecture me on how my constipation was linked to my acne, and then he would tell me some story from his Chinese newspaper about a woman who married a bad man and then died some horrible death!

So, when I was growing up, I was basically convinced my dad was a crazy person.

Living in Missouri, that’s how he always seemed to me. And that’s kind of how he seemed to everyone, especially as he got older and faced the double discrimination of being Chinese and being elderly. Nurses and doctors, restaurant wait staff and bank tellers all seemed to share my impression that my dad was just an eccentric and foolish old Chinese man, and that’s all there was.

Dad passed away this past June at the age of 88. About a year before he died, as he requested, I took him back to live on Taiwan, where he had spent most of his life. He was a military veteran, and I thought we could get him into a veterans home on Taiwan, where he could spend time with other people with similar experiences.

When we arrived in Taiwan two years ago, we stepped off the long flight at the Taipei airport, and I got Dad into a wheelchair, and we headed to the gate. As soon as we got into the airport, before customs or immigration, with everyone else’s loved ones and rides being held by gates and security way at the other end of the building, this man walked right up to us and said my father’s name. He then took over my dad’s wheelchair for me and pulled out his card to show me who he was. We didn’t know this guy. But he had come to greet the old man with the American daughter.

So I later found out that the equivalent of our Secretary for Veterans Affairs–a cabinet level person in the Taiwanese government–had heard that my father was returning from the United States, and he had personally sent a representative to meet us at the airport and guide us through immigration and customs. The next day another representative from Veterans Affairs picked us up, and, for the next week, he took my father and me to doctor’s visits, to appointments with veterans’ benefits offices, and nursing home scouting. And, for that week, we were invited to stay in a guesthouse at the university where my father served many years as chief accountant, and all these people there people remembered him as a competent leader and a respected boss. They treated us like royalty…because of my dad.

It was really cool, but it was also really sad because I noticed how jolting it was for me to see people treat my dad with respect.

When I look back on the almost thirty years I spent knowing my father as a Chinese immigrant in a very white and homogenous part of the United States, it pains me to say that I had never before seen him treated with honor and deference. Because where I grew up, my dad’s accented English, Asian features, and unique customs distracted all of us–including his own daughter–from knowing who he really was: this interesting, intelligent, and accomplished human being with rich and complex life experiences.

As is true with so many who come to this country from abroad, I could only see my father as he really was when I allowed myself to venture into the spirit of his homeland, where red envelopes, meditative practice, and traditional Chinese medicine were not eccentric and strange, but were part of a rich cultural heritage full of meaning and beauty and struggle. And today, as I continue to remember and grieve for my father, it is those things that I used to hink foolish, which I now mine for meaning and hold most sacred.

It is not unlike how we experienced Jesus among us. Jesus too made a journey to our world from a foreign kin-dom. He too was a misunderstood immigrant with his strange heaven-grown accent and customs. He too probably embarrassed his family and friends with his eccentric behaviors. They couldn’t take him anywhere–the synagogue, dinner parties–without him saying or doing something uncomfortable.

Jesus was definitely not from around here. While other revolutionaries called for swords and blood, Jesus called us to “love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us”. While other leaders expected to be served, Jesus washed the feet of his disciples and laid down his life for them. While other oppressed people saw death on a cross as a defeat, Jesus made it into his greatest victory.

And, like my dad left me with memories of strange rituals from his homeland, Jesus taught us a few of his native customs.

Like the bath where God claims us as beloved no matter how dirty we feel. But he also taught us other-worldly customs that seem more than strange–almost repulsive–to those of us too native to this world. The adoration of the cross, which–as Paul says–was foolishness to the Gentiles and a stumbling block to the Jews. Perfectly reasonable reactions since this thing we bejewel and guild and hang in our sanctuaries and hold precious around our necks was a device of Roman torture, humiliation, and oppression. Pretty offensive. And then there is the meal we will eat together today, where we remember and hold sacred for all time the night when everything fell apart for God, when Jesus was betrayed and abandoned. And we would have fled too. He had lost it, asking us to eat his flesh and drink his blood. Eucharist is tuly a ritual from another realm that, even today, I understand just about as deeply as I understand Lunar New Year and the customs of my father.

And yet, these customs have become most sacred to us. Long ago, we looked at Jesus eating with sinners and hanging on a cross, and we saw an eccentric, foolish stranger. Many of us still do. But, for those of us who have glimpsed his kin-dom, who have taken the time to learn its language and customs, who have traveled to its shores through prayer and worship and study and action….those of us who have been immersed in the waters of grace, who have communed with our enemies, who have found–like Frank Schaefer and Tom Ogletree and others who have been on trial for their ministry–that God can turn any cross into victory…We have seen the eccentric fool in his native land, where the fool is royalty, where water is wisdom, the meal is revolution, and the cross is salvation. Thanks be to God.

18For the message about the cross is foolishness to those who are perishing, but to us who are being saved it is the power of God. 19For it is written, “I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and the discernment of the discerning I will thwart.” 20Where is the one who is wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the debater of this age? Has not God made foolish the wisdom of the world? 21For since, in the wisdom of God, the world did not know God through wisdom, God decided, through the foolishness of our proclamation, to save those who believe. 22For Jews demand signs and Greeks desire wisdom, 23but we proclaim Christ crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles, 24but to those who are the called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God. 25For God’s foolishness is wiser than human wisdom, and God’s weakness is stronger than human strength. 26Consider your own call, brothers and sisters: not many of you were wise by human standards, not many were powerful, not many were of noble birth. 27But God chose what is foolish in the world to shame the wise; God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; 28God chose what is low and despised in the world, things that are not, to reduce to nothing things that are, 29so that no one might boast in the presence of God. 30He is the source of your life in Christ Jesus, who became for us wisdom from God, and righteousness and sanctification and redemption, 31in order that, as it is written, “Let the one who boasts, boast in the Lord.”

I Corinthians 1:18-31

Comments are closed, but trackbacks and pingbacks are open.